There were a number of influences that came together leading to the creation of “New Fun #1.” Like many people during the Depression, Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson suffered a loss of income and needed to take care of his family, which by now included five children. His pulp adventure writing was no longer enough so instead of looking for a job he decided to create a company. Doesn’t everyone do that?

New Fun #1

The logical business for the Major was a publishing venture but after his experience in the newspaper syndicate business and with the pulps not paying enough he needed something unique. According to Lloyd Jacquet, the Major’s first editor who would go on to a long career in comics as an editor and publisher, the Major had seen the weekly comics magazines that featured original material throughout Europe and thought this kind of magazine might do well in the United States. Jacquet stated, “He also knew that the American presentation of such material would have to be different, and merely importing or translating European-produced features for republication here was not the answer. That is why he was not unduly concerned when he saw a British paper called “Comic Cuts” appear on the newsstands.” 1)

“New Fun #1” is not a copycat version of the British “Comic Cuts” nor is it a wannabe reprint from newspapers. The idea from the very beginning was to create something unique. MWN was a strategist and before undertaking any endeavor he considered all the possibilities. His earlier foray publishing through his newspaper syndicate in 1925-26 indicates that the idea for a comics magazine was already percolating. He not only published comic strips in panels but also a full page of comics and adapted stories from the classics in comic book form such as Ivanhoe, Treasure Island and The Three Musketeers. A person who takes an enormous risk in the midst of a Depression to create something entirely new is hardly the type of person to do so just because he couldn’t get rights to newspaper comic strips to reprint. Let’s please retire that old myth. It is demeaning to the tremendous effort and energy that the Major put forth in his comics venture.

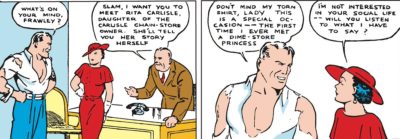

The Major was a creator throughout his life. He chafed under the bureaucracy of the military constantly advocating new ideas and ways to modernize the army. Although the military was ultimately not a good fit for him, it did prepare him for later endeavors in many ways. He was an extraordinarily disciplined person for one. And it helped to hone his natural talent for leading especially in regard to collaborative creative efforts. When he began to work with Siegel and Shuster, the Major gave them a number of ideas such as “Slam Bradley,” “Federal Men” and “Calling all Cars” and he had the respect for their ability to execute these ideas. Further his editorial suggestions in letters to Siegel are subtle and respectful.

Slam Bradley created by MWN and Siegel and Shuster.

The primary difference between the Major and most other publishers who followed in his wake is that he was a creator unlike Harry Donenfeld, Jack Liebowitz, Martin Goodman, John Goldwater and others who were all involved with the business end of publishing and printing. The Major was unique in this regard at the very beginning of the industry. There were other publishers who came later that were also creators such as Will Eisner but the Major led the way.

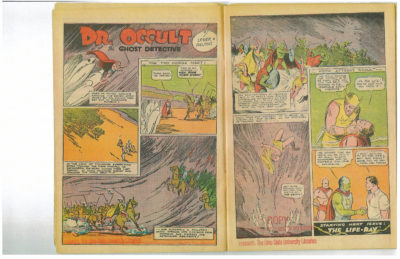

Because he was a creator himself, MWN followed the pulp practice of “first American Serial Rights,” which generally meant that once a piece was published then the creator retained the rights. MWN stated this in a letter to Jerry Siegel regarding Dr. Occult. “Strictly speaking Dr. Occult belongs to you and we will release all rights to you other than first serial, any time you so desire.” 2) At the beginning of the industry MWN advocated creator’s rights.

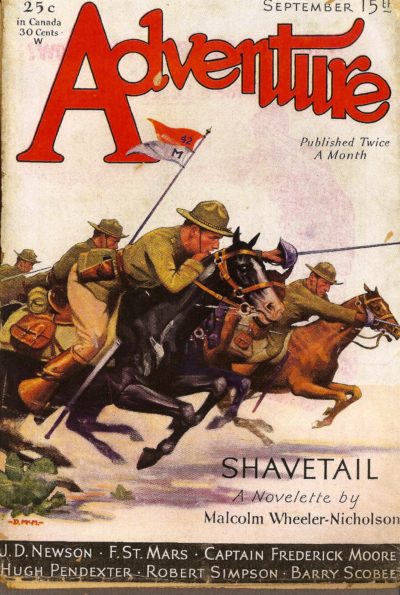

The Major’s creative hand is all over “New Fun #1.” One of the unique aspects of the Major’s comics magazines is their evolution from the pulps. As Lloyd Jacquet noted, “Now we had a little book shelf in the Major’s office, in lieu of files, and on it were placed some of the new ideas which were constantly cooking up for our new-found magazine business. These ideas were rough dummies of other comic books that we wistfully wished we could publish. Major Nicholson’s pulp background helped here, for it was a natural step from the “general” title of comics (of the funny type, incidentally), to the western, and the detective, aviation, and so forth, that were even then the backbone of the pulp mag sales on the newsstands all over.” 3).

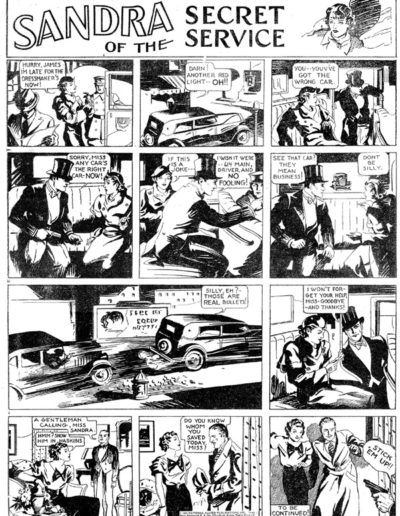

It’s not surprising that the pulps played an important role in the development of comics since pulp stories have heroes, heroines and storylines that easily translate to comics panels. Barry O’Neill, appearing in “New Fun #1” and considered to be DC’s first action hero, began life in one of the Major’s pulp stories. “Sandra of the Secret Service” appears to have been created by the Major as well and is typical of his heroines being beautiful, smart, able to ride and shoot well and take care of herself in difficult situations.

Like many of you I’m anxiously awaiting the release in early April of DC’s special anniversary reprint of New Fun #1. I contributed an essay on the Major and short bios of all the contributors. Roy Thomas wrote the Introduction and we’ve included Jerry Bails introduction intended for an earlier reprint that did not make it to publication. It’s going to be thrilling to finally hold it in my hands. Because these early magazines are rare most people have not seen them. It will make a big difference in the way comics historians, journalists, and fans view this beginning of DC Comics to see an exact reprint of the original.

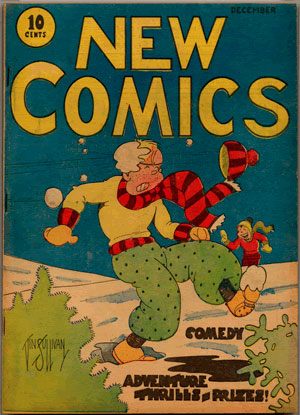

The first covers of “New Fun #1” through “New Fun #6” were tabloid size and featured a full-page comic story consisting of 4 panels. By December 1935 the second magazine the Major published, “New Comics #1” was no longer tabloid size and had a full-page cover illustration. “More Fun” soon followed the same format by March of 1936. And by the time Creig Flessel was drawing covers for “Detective Comics,” the covers were a unique combination of the action of pulp magazine covers in cartoon style.

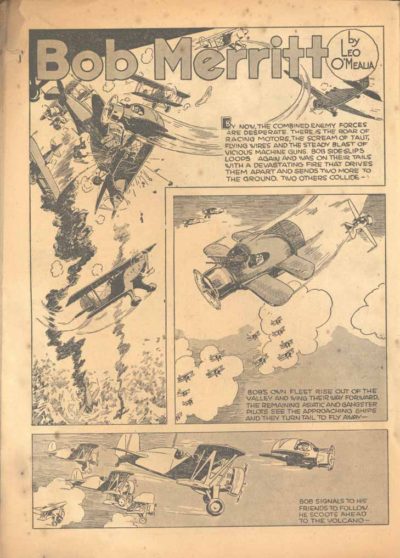

The interior pages of “New Fun #1” and #2 were in black and white followed by some comics in color in “New Fun #3.” Innovations in the artwork appeared fairly soon. With the ability to work on a full page or a three-quarter page, artists moved away from the strict format of newspaper strips. The manner in which panels were organized helped to tell the story as can be seen in the Bob Merritt strip in “More Fun” drawn by Leo O’Mealia.

“New Fun #1” had a number of non-fiction articles and one fictional story—a sort of hybrid between the idea of a newspaper and a comic book. Within 2 years by February 1937 with the appearance of “Detective Comics #1” on newsstands we now have a comic devoted to a single theme and appearing much like comics today. In those years from 1934 to April 1938 the Major created characters, comics, wrote perhaps around 450 scripts, developed 4 magazine titles including “Detective Comics” publishing 63 magazines, discovered talents like Siegel and Shuster, Bob Kane, Creig Flessel, Sheldon Mayer, Vincent Sullivan, Whitney Ellsworth and Walt Kelly among others. It was a phenomenal surge of energy that helped to found an industry.

My wish is that comics scholars, journalists and others who teach and promote comics will take the time to look at “New Fun #1” and begin to see the through line that leads right up to “Action Comics #1.” There is a continuum from “New Fun #1” to what we consider the modern comic book and it all happened in just three short years. “New Fun #1,” thanks to the Major, is the foundation of DC comics and where the entire modern industry got its start.

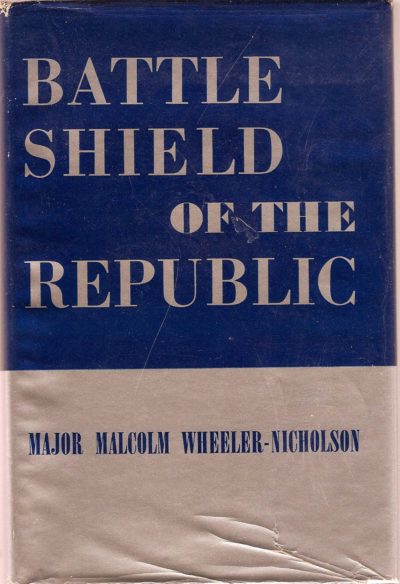

After the Major lost his comics company to his partners in a forced bankruptcy he went on to write about real heroes during World War II publishing three non-fiction books on politics and military strategy and numerous articles in Look, Harper’s Magazine and many others. He also continued writing adventure stories for the pulps.

His last creative endeavor may have been the closest to his greatest dream as a “gentleman inventor” like his character Bob Merritt. In 1948 on a trip to Sweden he discovered a formula for industrial paint, developed it and patented it and other patents for building construction. He continued writing almost every day of his life. The Major died September 20, 1965 and is buried in Nassau Knolls Cemetery in Port Washington, NY. It was an amazing life.

1). Lloyd Jacquet, “The Coming of the Comic [Book],” Newsdealer (July 1957), reprinted in Comic Book Marketplace #88 (December 2001).

2). Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, letter to Jerry Siegel, March 16, 1937.

3). Jacquet. Ibid.

Amazing history. I love this.

Thanks! If you’re on Facebook, you might be interested in the Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson Group. It’s a lively group with a number of comics historians and authors. We’d be glad to have you.