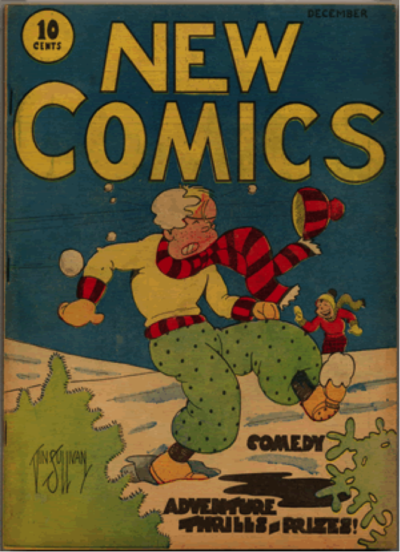

This is a continuing look at DC Comics beginning with New Fun #1, January 11, 1935.

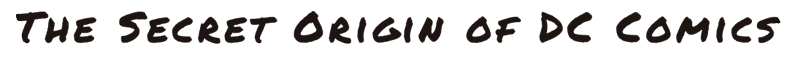

A number of changes occurred between the appearance of New Fun #4 on newsstands, April 12, 1935 and the appearance of New Comics #1 on November 12, 1935. Although in hindsight there is a sense of shaky foundations there is also a surge of creativity that is evolving notably in New Fun #5 with the appearance of Siegel and Shuster. Followed by New Fun #6 and then New Comics #1, the second title published by National Allied Publications, Inc.–DC’s predecessor–the contents of New Comics #1 are bursting with new ideas and new talent including Walt Kelly and Sheldon Mayer. No longer tabloid sized and with a single scene on the cover New Comics #1 begins to have the appearance of a modern comic book.

DC began as National Allied Publications in 1934. Their first comic New Fun #1 hit the newsstands on January 11, 1935–86 years ago. The year 1935 continued with New Funs 2, 3, and 4. Tabloid sized featuring a comic on the cover, similar in style with similar content the masthead remained the same for the first 4 issues with Lloyd Jacquet as Editor and Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson as publisher, Dick Loederer as Art Director, H.D. (Henry Dwight) Cushing as Advertising Manager and Rexford L. May as Circulation Manager. The magazines were distributed by S-M Newsstand Distribution Co.

New Fun #1

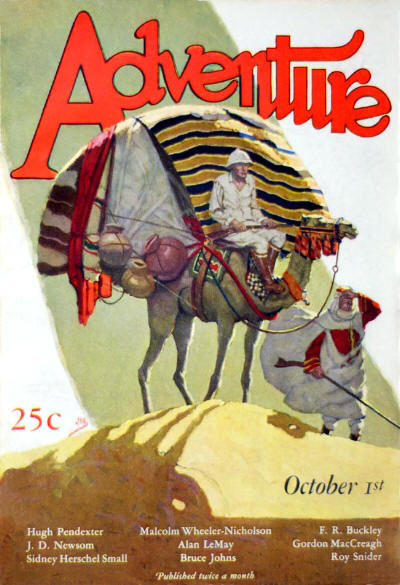

The covers were in color and the interiors were black and white with some interior color added by New Fun #3. The magazines contained all original material unlike the reprints of newspaper comics that were available. The comics were aimed for a wide demographic. There were noir comics based on pulp stories like Wheeler-Nicholson’s pulp story hero, Barry O’Neill—considered DC’s first action hero. There were comics aimed for teenagers like “Jigger and Ginger” by Adolph Schus and lots of comics for children plus articles and activities. Lloyd Jacquet was the editor for the first 4 issues and they rolled out on a regular schedule for 4 months and by the second issue were publishing excerpts from the fan mail that was coming in. Going sequentially through the magazines gives one a sense of growth and change and the excitement building that was evident in the fan mail.

New Fun #3

After New Fun #4 appeared April 12, 1935, there was a period of 3 months before New Fun #5 appeared on July 12, 1935. Lloyd Jacquet was no longer editor and “the Major” was now acting as both Publisher and Editor. In the forced bankruptcy proceedings in 1938 the Major stated that they were normally working about 3 months ahead.

New Fun #4

In order for New Fun #5 to appear on newsstands a month after New Fun #4 around May 12, 1935 they would have started with the ideas for the cover and content sometime in February 1935. What occurred over those months or suddenly at the last minute that caused the gap? The main three production issues for publishing a magazine are available content (which I’ve been writing about throughout theses posts), printing and distribution. Initially the printing occurred through the auspices of The Brooklyn Eagle and distribution through the powerful S-M Newsstand Distribution Co. with their logo located in small print in the upper righthand corner of the cover. According to Jacquet the first issue of New Fun #1 sold about 50% and as Todd Klein notes in his blog on the DC offices that’s good for a new magazine so where was the difficulty?

David Saunders, focusing on the publishing of pulp magazines has done extensive research into the web of distribution and printing companies and their connections existing during this period to mobsters. It’s not surprising that these same companies became part of the comics industry. With few clues from the documents that exist one can only surmise what caused the difficulties.

Obviously, the Depression itself was a factor as well as the connections between organized crime and distribution. On April 28, 1934, just months prior to the establishment of National Allied, S-M Newsstand Distribution, Inc. was one of three distribution companies along with five publishing companies cited by the Federal Trade Commission for conspiring to destroy the second hand and used magazine periodical business. The irony should not be lost that these companies’ magazines including those of Frank A. Munsey and Street and Smith, would become some of the most sought after many years later in second hand magazine collecting. This event indicates the intricate connections and power wielded in the publishing and distribution industry. S-M continued to distribute New Fun #5 and 6.

Lloyd Jacquet had been a writer for The Brooklyn Eagle since his youth. Although Jacquet left after New Fun #4, Cushing and May continued through New Fun #6. Connie Naar who also wrote for The Brooklyn Eagle is listed as the Assistant Editor in New Fun #5 and continued to contribute stories and illustrations into 1936. That would indicate there was no problem with the association with The Brooklyn Eagle. Jacquet spoke about the Major quite favorably in a July 1957 article for the trade magazine, The Newsdealer reprinted in Comic Book Marketplace in 2001. Jacquet hints at what may have occurred. “But Major Nicholson’s quiet determination and resourcefulness in the face of many odds and situations pushed the whole thing along until his progress started to be known by others. Then the real fun began—but that’s another story!” That would leave distribution as one possible problem.

The indicia in New Fun #5 states the office of publication as 420 DeSoto Avenue, St. Louis, Mo (World Color Press) instead of 307 Washington St. Brooklyn. It is entered as second-class matter at the post office in St. Louis. The printing was now being done by World Color Press who became a significant player in what later transpired. What caused the change in printers? Was it purely a financial decision?

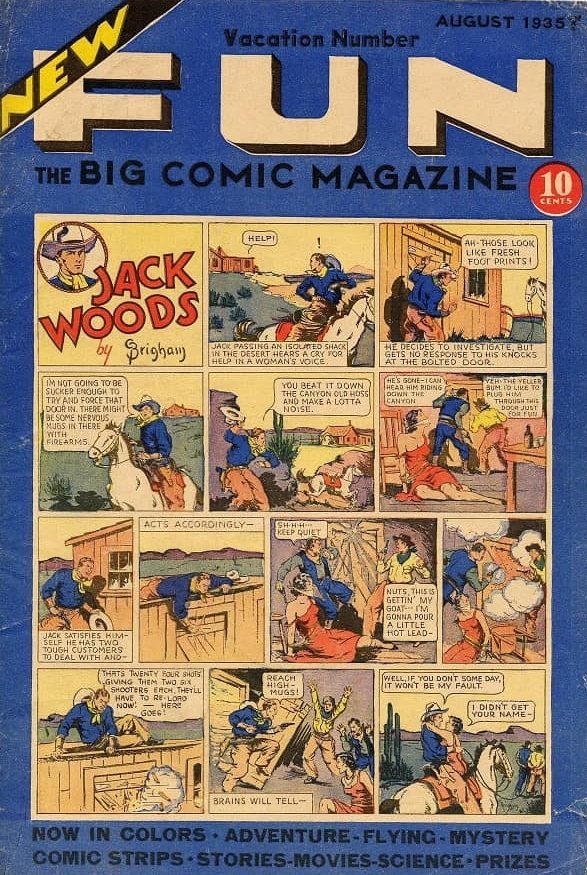

When New Fun #5 came out on newsstands on July 12, 1935 “Vacation Number” was above the Fun logo and in the editorial content it was explained that the magazine had been enjoying a summer vacation. I doubt anyone involved was taking a vacation. To be fair this endeavor was a completely new idea being birthed in the midst of the Great Depression. That they managed to continue forward in spite of whatever difficulties is a testament to Wheeler-Nicholson’s “quiet determination.”

New Fun #5

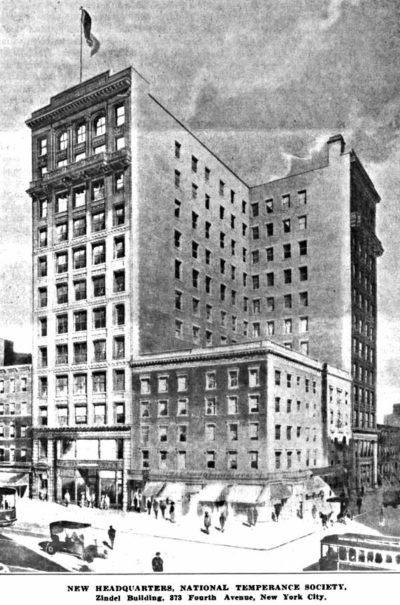

In addition to these changes, the editorial office was moved from 49 West 45th Street to 373 Fourth Ave. (Park Avenue South), sometime between July 12, 1935 and September 13, 1935 when New Fun #6 was published. 373 Fourth Ave. was, coincidentally, where, in May 1926, the Major housed his earlier publishing company, Wheeler-Nicholson, Inc. Newspaper Syndicate.

Illustration from “The National Advocate,” 1912. From Todd Klein.

By New Fun #6, Richard Loederer who had been Art Director for the first 5 issues of New Fun was replaced by Tom McNamara. Loederer is instrumental in the look of the New Funs from the logos above features to his own comics and various fillers throughout. It’s clear from the glowing editorial write-up he was given in New Fun #5 as a farewell that there was no ill will between him and the Major. Connie Naar continued as Asst. Editor with William H. Cook as Managing Editor. There’s more to learn about Cook throughout 1936.

New Fun #6

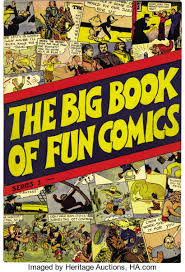

In New Fun #6 there is an ad for The Big Book of Fun Comics—48 pages at your nearest 5 and 10 cent store. The Big Book of Fun Comics is considered by some to be DC’s first annual. It is very rare. I have not seen a copy and what information I was able to gather came from a few scans of the cover and some interior pages and from the more erudite members of the MWN group. There is some information listed about the contents on The Grand Comics Database. Although there are sometimes mistakes here and there on this gigantic comics database they are rigorous and I trust the information.

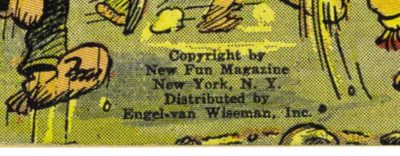

Some comics history sites list The Big Book of Fun Comics as being available October 11, 1935. That would be about a month after New Fun #6 was on newsstands on September 13, 1935. The Big Book of Fun Comics was tabloid size, and the cover was a compilation of various comics in color from New Fun #1-4. There was production involved as some of the comics that had originally been in black and white were now in color according to those who have seen a copy. The inside covers were blank and there was no indicia and no ads. The only indication of copyright was on the back cover in the bottom left-hand corner. “Copyright by New Fun Magazine, New York, N.Y. Distributed by Engel-van Wiseman, Inc.” As far as I know there was no corporation New Fun Magazine, Inc. just the magazines themselves that were published by National Allied Publications, Inc.

Besides the curious copyright there are other questions raised by this “annual.” Why was it distributed by Engel-Van Wiseman, Inc. instead of S-M Newsstand? Engel-Van Wiseman was founded by Jerome van Wiseman and George Engel who were in advertising. They published song folios and got into Big Little Book publishing a number of books in 1934 and 1935 based on current films. According to Dennis Gifford The Big Book of Fun Comics was “…sold at 10 cents in F. W. Woolworth stores, rather than on newsstands.”

The other question is why were some comics from New Fun #1-4 included in The Big Book of Fun Comics and others were not? Some decisions must have been based on encouraging readership so it is logical that comics that only appeared one or two times were not included. Also, by the time this was put together there was an awareness of the comics that the fans liked from the fan mail. However, there are some choices that don’t quite make sense unless they are possible creator/ownership issues including those of the Major.

Most of the comics included have the full run of their stories with a few exceptions. “Don Drake on the Planet Saro” (Fitch/Gretter) leaves out episode 3. However that episode appeared on the cover of New Fun #3. Was it a problem to obtain the plates? Or was it difficult to reproduce? The other Fitch/Gretter comic “2023: Super Police” included all 4 episodes.

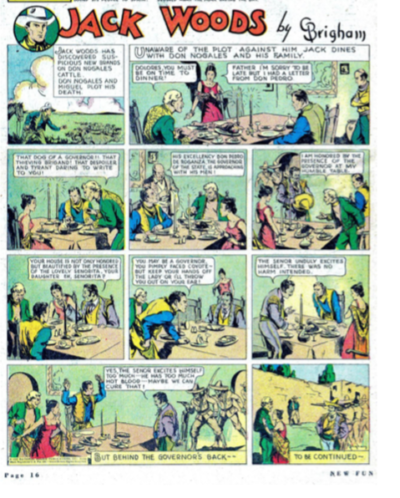

“Jack Woods”, “Sandra of the Secret Service” and “Barry O’Neill” were all popular with the fans. However, episodes 1 and 2 of all three of those comics were not included. “Jack Woods” was drawn by Lyman Matthew Anderson in New Fun #1 and #2 and then drawn by William Clarence Brigham, Jr. for the rest of the run. There is some confusion about the scripts for “Jack Woods.” I initially thought it followed a similar pulp story of the Major’s but there is some evidence that it may have been taken from a film. However, the story abruptly changes in episode 3 that more closely follows one of the Major’s pulps. I’m still on the trail.

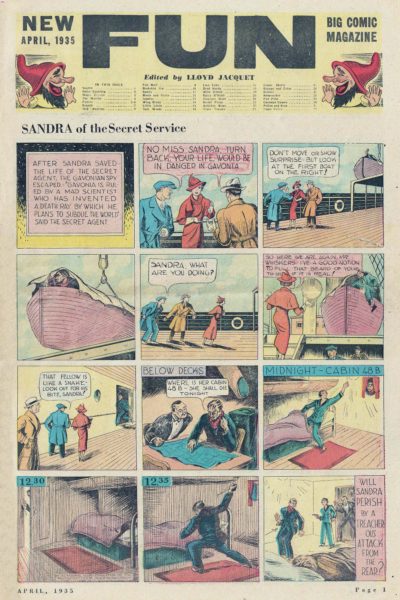

“Sandra of the Secret Service” had no signature in New Fun #1 but is attributed to Charles Flanders. He is credited in New Fun #2. There is no signature in New Fun #3 and the artwork is clearly not that of Flanders. Moe Eisenberg is credited in New Fun #4 and these last two episodes were included. Ivanhoe drawn by Flanders in 1, 2, 3, 4 is included. “Sandra of the Secret Service” was drawn by a number of artists throughout the run but the one person who was the through line was MWN. Some of the scripts are attributed to him and for many reasons I am fairly certain he created this character.

From New Fun #3

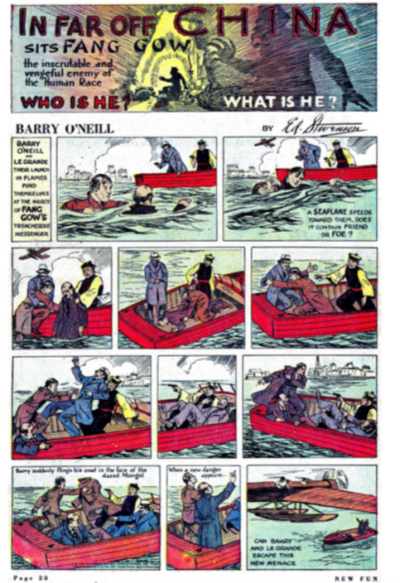

“Barry O’Neill,” originally drawn by Lawrence Lariar in New Fun 1 and 2 is not included but episode 3 drawn by Ed Stevenson and episode 4 drawn by Leo O’Mealia is. The heading of the story changed in New Fun #3 with the 3rd episode. Instead of the simple “Barry O’Neill” it had an ornately drawn heading “In Far off China sits Fang Gow, the inscrutable and vengeful enemy of the Human Race. Who Is He? What is He?” Barry O’Neill and Fang Gow are characters created by the Major and the plot follows a similar plot in a pulp story MWN wrote with Fang Gow as the villain.

From New Fun #3

The Major followed the pulp magazine practice of creator rights by publishing creators’ works under North American Serial Rights with the rights returning to the creator once originally published. This could be a possible reason for not including some of the episodes from these comics. In the forced bankruptcy proceedings in 1938, the Major persistently supported creator rights.

Examining these details as we go through the comics can provide some clues about the legal and business aspects of the magazines. The consistent part of the Major’s story told by others always ends with him being a poor businessman and that’s why he lost DC et al. It may be that he was a poor businessman. If so, specifically how? The classic battle between the creators and the accountants is evident at the very beginning of these comics.

There is a double standard in regard to creator rights and who is and is not considered a good businessman. The entire history of modern comics is filled with the mythic tales of creator rights beginning with Siegel and Shuster. At the same time as far as I know, no one questions the business acumen of Donenfeld and Liebowitz. The conclusion therefore is if you are able to make large sums of money from the creative work of others then you are a good businessman.

Whatever the financial situation happened to be it is clear that the creative end of the business was in full bloom by New Comics #1. More to come.

Special thanks to David Saunders, Todd Klein, Rod Beck, Bob Beerbohm, Bob Cherry, Jim Davidson, Bob Hughes, Frank Motler, Daniel Ripoll, Steve M. Russo, and Jim Van Dore for their contributions.