Recently I interviewed Kim Munson about her book Comic Art in Museums. Although it is not directly connected to the Major’s work, I found it to be an excellent reference for discussing the art in the Major’s early syndicate 1925-1927 and the art in New Fun, More Fun, Adventure and Detective Comics 1935-1938.

Nicky Wheeler-Nicholson (NWN): This is Nicky Wheeler-Nicholson. And today I’m talking to Kim Munson about her book, “Comic Art in Museums.” Kim is an artist and an art historian. She’s also my friend and colleague and knows a lot about comic art. Let’s just jump right in. I will say this book is really dense and packed with information. And even if you’re not museum director, if you’re just a fan, this is a great book. It has a lot of interesting aspects to it for anyone who loves comic art. So, Kim, what brought you to this particular path, museum exhibits and comics and how does it lend itself to Comics Studies?

“Comic Art In Museums” edited by Kim A. Munson. University Press of Mississippi, 2020. 386pp, 80 images. Hardcover, Paperback, E-Book. Press Release, Excerpt.

Kim Munson (KM): Well, that’s a big question. Could I break that question in two? First, what brought me to this path? After working for a long time, I finished my degree later in life. I did my BA at San Francisco State in 2006. When I decided to stay on for my Master’s in art history, I had different ideas about topics. I was doing works on paper, and I tried union labels and graphics and some other pop culture topics. I always loved comics and the “Masters of American Comics” exhibit had just happened in LA and the catalog was great. But one of one of the things that they were saying in the press was that “this was the first time this kind of show has been done” and I just knew that wasn’t right. We’ve had the Cartoon Art Museum here in San Francisco since the 80s. So, I started researching and it became my thesis. Then I just kept going. I started in 1983 with “The Comic Art Show” and now I’m all the way back to the 30s and still working on it.

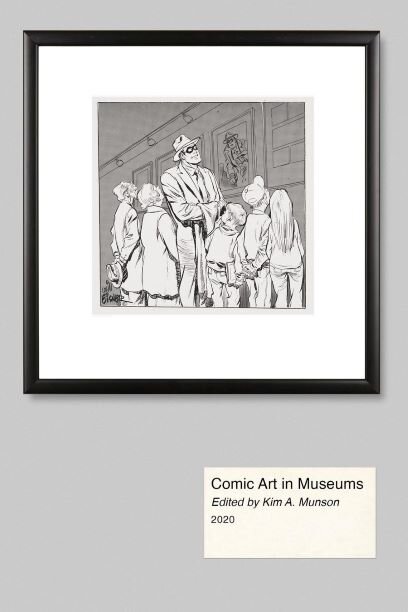

This 1942 exhibit was first known show in the US to put Comic Art in an Art Historical progression with museum quality Ancestors like Mayan panels and Japanese Scrolls, curated by Jessie Gillespie Willing, a female magazine illustrator. Toured to many US cities. “Comic Art in Museums” includes new research about this show from Milt Caniff’s papers at The Billy Ireland, The AIGA Archives, and many other sources.

As to the second part of your question about the background in art history. I’ve had art jobs throughout my whole career. I started out as a theater kid doing community theater. I always painted sets and all of that stuff. I moved to LA in 1979 and worked as a scenic artist in Hollywood for 10 years. Then I moved up to San Francisco. And I worked during the first dotcom wave as a creative director for a couple of different websites and for Oracle and Autodesk, and a bunch of companies like that. In 2000, when the industry wide layoffs came, I decided to go back to school and finally finished my BA in art history which was a common thread that tied together all of the research and creative work I had been doing. It was a great fit. So, in terms of comic studies, there are not many art historians involved in comic studies. Art history is something that’s just recently started to be applied. Most of the comic studies people in academia are hired by English departments, so comics studies really started with analysis of comics as literature. For a long time, there were only five or six of us that were actually writing about the artwork, and the exhibition thing is really new. Some scholars have included a chapter here or there that mentions some exhibits. But I’m the first one that put together a chronology that ties comic art into the history of all the different art movements going on in the US and how comics kind of waxed and waned with the shifting interest of the larger art world.

NWN: One of the things I loved about your book is that I learned a lot, even though I spend a lot of time with art in early comics. What was your original intention in writing the book?

KM: This book originally started out as a reader, which I proposed a bunch of times with Michael Dooley as a co-editor but no one ever went for it. Back when I was working on my master’s, my thesis committee had no idea that comics scholarship existed. I had to bring in The International Journal of Comic Art, the Masters of American Comics catalog, and whatever else I could find to convince them that yes, academic study of comics was a real thing. After going through that experience, I realized that there was nowhere that any of the important reviews and other commentary were collected in this type of book. I basically wrote the book that I needed when I was working on my thesis, and I hope that it’s useful for curators because a lot of the time museum people have an idea, but they don’t really have the intellectual arguments for how to set it up and talk about the artwork in a good way. Hopefully, this is giving them background on how to curate good exhibits of this particular art form.

NWN: It is, to use a cliché, it is a groundbreaking book for sure. Absolutely. What are you most passionate about? For the book and writing the book? What is the most passionate aspect of it for you?

KM: You know, in my own small way, I wanted to end the high and low argument because I’m really tired of hearing about it.

NWN: Explain what the high and low argument is.

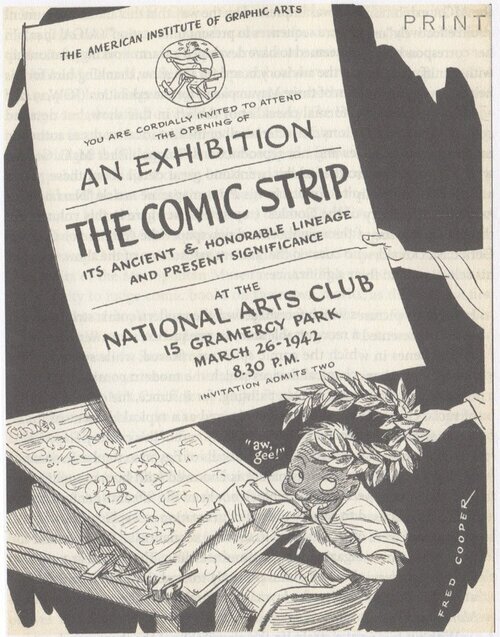

KM: Comics have always been sort of frowned upon. In this case, I’m talking about the period when Modernist painting was really coming in, there was an influential art critic named Clement Greenberg, who wrote that comics and the other industrial arts like magazine illustration, and animation were kitsch. The idea was that this was artwork that was really popular with people but distracted them from contemplating higher things. This was the whole underpinning of the abstract expressionist movement for example, artists like de Kooning and Pollock. The whole post war New York art scene really embraced these paintings and made a lot of money from it, and the larger art world ignored representational art for a long time. Comic art disappeared from museums after WW2 into the 50s and 60s. Museums were really focused on these giant abstract paintings, nothing else really mattered. It was a struggle just to get traditional representational artwork into museums much less like something like comics, which were pretty far down the totem pole.

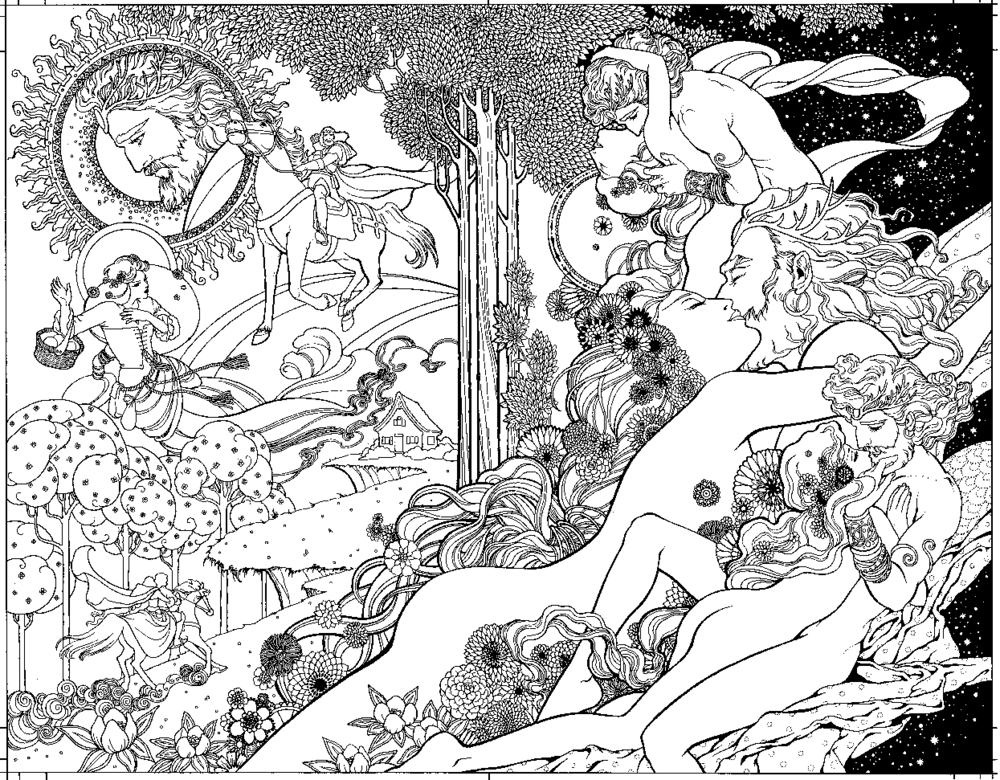

“The Myth Recycled” by Jonah Kinigstein uses the classical form of the Laocoon and his sons to satirize the artists, museums, and galleries that appointed themselves the gatekeepers of the NY Art World. Karen Green interviews the artist in Comic Art in Museums.

NWN: What is it about comics that attracts you, and who are some of your favorite artists?

KM: Well, my husband and I are big collectors. He’s a law professor and attorney that specializes in IP. And he represents a lot of comic artists in various matters. We have a big art collection of work from his clients or art that we’ve bought at Comic Con, or whatever. Tons of books, statues, and action figures. I generally have a soft spot for mythological characters like Wonder Woman and Thor. Comic art is something I actually live with every day.

Since I’m curating and researching, it’s kind of like I love whoever I’m working on at the time. In the book, for example, I did a lot of research at the Billy Ireland and discovered completely unexpectedly that Milt Caniff was an early pioneer of comic art exhibits, so I got really into his artwork because I was writing about him all the time. Now, I’ve got a show about women in comics, which features the great historical collection of art by women cartoonists belonging to Trina Robbins, as well as lots of great modern cartoonists, and so I love all of those women. So, I love all kinds of things and my interests shift with the focus of my research. I wouldn’t call myself an expert on any particular era.

Colleen Doran’s illustration for Neil Gaiman’s “Snow, Glass, Apples.” One of the many outstanding works in “Women in Comics.” Colleen was inspired by the stained glass art of Harry Clarke.

NWN: Oh, that that’s good, because you keep an open mind when you’re working on exhibits, which is really important.

KM: I think it keeps me open to recognizing the interconnected nature of things. I can compare something really modern and something really old and find the bridge between them.

NWN: How did you decide on the various sections of the book and the people you include it?

KM: There were a couple of parts to that process. Since I was originally thinking of this project as a reader, I collected articles for a long time. First, there were the historical essays that I picked. Through my research, I found exhibits that I thought were essential for people to know about and I found historical essays that were reviews of those shows by influential critics or some other important commentary from that era. Through my own set of connections, I knew people that were writing scholarship in other areas of interest. So that was part of it. And then, as I went through it, I found gaps and things that I thought were important to talk about. In those cases, I interviewed people, like Art Spiegelman, Carol Tyler, or Joe Wos. In some cases, I specifically invited certain people, like Denis Kitchen for the overview or Karen Green’s interview with Jonah Kinigstein. It was a process with a lot of scattered parts coming together.

Denis Kitchen explains Will Eisner’s drawing techniques at the Society of Illustrators in New York.

NWN: You mentioned how the University of Mississippi press process worked in terms of the book. Do you want to talk a little bit about that? How the book came together with them? And the review process?

KM: Yeah, well, there were a couple things. I regularly present at the Popular Culture Association’s national convention so, I had seen Mississippi Press quite a bit and talked to the editor there because they always have their table. When I first asked them about it they weren’t really interested in a reader about comics exhibits and I was an unknown author. Over the course of researching several articles, I’ve gotten to know Brian Walker and he’s kind of mentored me a bit. A couple of years ago, Brian said, “Mississippi Press keeps asking me to do a book, but I don’t really have time, why don’t you propose that reader project, and I’ll contribute a couple of essays.” So, Brian really championed this book with Mississippi. Another was Tom Inge, who’s on their board and does a couple of series for them. He did a really important exhibit around 1970. He said “This is a great topic, we should do this.” The press was also encouraged because they had done a couple of exhibit catalogs that sold well. The press still took some convincing though, so it would not have happened without help from Tom and Brian.

In terms of process, peer reviews turned out to be very important to me. In my first draft, I organized all the essays chronologically. They weren’t arranged thematically, the way they are now. When I got peer reviews back, I gave a lot of thought to the input that I was getting from people, and why they were confused about certain things. It really helped me clear things up and articulate the chronology in a way that made sense. I reorganized it into thematic chapters to tie things together so the narrative was clear. For example, there’s a chapter about the group of artists and curators that came together to do Masters of American Comics as a response to High and Low at MoMA and all the critical reaction that generated. This way it’s easier for people to figure out why these things are included together.

NWN: There are some essays that are highly academic in nature, and they reference art history that general readers may not be familiar with. And then there are other essays that are very accessible for people who are just simply interested in the history of comics. Are you hoping that the more accessible essays will be entry into the more formal academic essays?

KM: Yes. When I interviewed Joe Wos, the former director of the ToonSeum in Pittsburgh, he was talking about community involvement and said that he had this concept of “broccoli with cheese” to draw in kids and other visitors. He said, “if you put enough cheese on it, they’ll eat anything.” It was his way of getting kids into the museum to see Superman or something familiar and then have them stay for a more complex show in his second gallery. But in general, since I’m aiming this at grad students and curators, they need that Art History background. I was lucky to find so many thoughtful essays written by people that can explain their ideas in plain language. So, if you’re diligent about it, you can get the highlights of those essays, even if you’re not an art history person. But they are really important contributions. If people can find their way into them it will be worth it.

Superman appears at the Toonseum in the 2011 show “Superheroes: Icons and Origins.”

NWN: Yeah, I think the book is set up very nicely in that way. Sometimes there’s something that’s very, very detailed for an art history person and then the next one will be something that is very easy to read and makes you think about the one you just read, which is really terrific.

KM: Thank you. Yeah, I tried to structure it so one thing built on the next. For example, in the beginning of the book, I have what I call the Foundations section. I have an overview by Denis Kitchen that’s the story of his experience and identifies some of the key issues. And then I have an essay that Brian Walker wrote for the opening of the Billy Ireland at OSU, that identifies who the most important artists were and explains the drawing techniques that cartoonists use. Then the art historian Andrei Molotiu has this great essay about how comics work as an art object on the wall, as opposed to a book and the differences of how the art is viewed. This is probably one of those technical art history things you’re talking about. But it’s a great lesson. It’s good background for people doing or writing about exhibits or for comics artists choosing which work to show.

NWN: Yeah, that one was a difficult one for me to get through. But I really liked it a lot. It opened my mind up to seeing the art in ways that I hadn’t seen it before. So yeah, that’s great.

KM: The principles Andrei talks about apply across art history. His essay is very specific to comic art, but a lot of these principles are things that are relevant to viewing any kind of artwork at an exhibition.

NWN: Most of the essays, in one way or another, depict the problems with comics exhibited in Fine Arts museums. How would you identify those problems? And do you think there are solutions to those problems?

KM: You know, comics exhibitions take a lot of thought because they have very specific challenges. Part of this is because comics are a sequential medium originally designed for a different use. They’re telling a story, usually, so there’s the idea of narrative, how much can you show so that the person viewing gets the gist of what the story was, because a lot of the time comic drawings don’t completely make sense out of context. They may be fabulous drawings, but you often need a little bit of story to understand what’s going on. Some shows, like Spiegelman’s “Co-Mix” or R. Crumb’s “Genesis” display entire books. In exhibit design classes, we are taught that people won’t read more than 250 words at an exhibit. So, it’s kind of a conflict. Curators and artists have to figure out what’s important to communicate about the artist’s work and what they think the audience can manage.

Art Spiegelman’s “Co-Mix” retrospective had his entire “Maus” showcased in a giant lightbox. Copies of the book were available at both ends of the bench and in the reading area at the end of the exhibit. In “Comic Art in Museums” Kim interviews him in depth about this show.

You also have to be careful when you exhibit comics, because there’s an issue of scale. A lot of museum galleries are set up for those big abstract expressionist paintings and larger artwork, so something like black and white 11 x 14 drawings can get really lost if you’re not careful. I mean, this is the same thing you have to consider if you’re doing an exhibit of Renaissance drawing. They’re not jumping off the wall at you like a big painting would be. So, you have to think about the space that you’re displaying the work in. These issues of scale and narrative are really important to think about.

NWN: But it also leads to a lot of innovation as well, in the way that exhibits are shown. That’s one of the things I found interesting in a lot of the essays were the way people, different people tackled those issues, and led to a lot of innovation.

KM: There’s one essay I included by a scholar named Damian Duffy, who writes about comics exhibits and new media. That’s important because more and more exhibitions are incorporating an iPad or something, so that you can see the artwork in various processes. Sometimes they show the finished book or give more background about it. Some shows, like the Gallery Comics shows Paul Gravett writes about, experiment with self-guided narrative. There’s also the idea Art Spiegelman mentioned to me while talking about Masters a while ago, where he was talking about the original concept that they had for the show. It was kind of a wheel and spoke idea where they would have a cartoonist who was a real innovator and then radiating from them would be the artists they influenced. And you could pick one of those people and get a fresh set of connected artists. It was too big of a show for them to do in those museums. But that would be a great multimedia show. One thing I’ve heard from artists over and over while working on this book is how influential it is to see other artist’s work in museums. For many artists, they’ll admire somebody, and then see their real drawing and it’s a real eye opener for them. So, I think the multimedia option is really important, especially since a lot of the work by older artists belongs to archives that may not want to loan the original drawings out.

NWN: Right. In the Joe Wos interview, I was particularly struck by his sense that cartoon art museums are not viable. And also, Brian Walker’s discussion of the same problems with the Museum of Cartoon Art. That was a great history of his father’s idea for the museum and how it worked. I loved reading that. And we’ve both been to MOCCA and to the Cartoon Art Museum in San Francisco. So, what do you think about Joe’s idea that cartoon art museums are just not viable?

KM: Speaking of Joe, this kind of goes back to the broccoli and cheese idea. I do think that museums that are specifically geared to comic art struggle, because there are some people that are just not into it enough to buy on-going memberships. The Cartoon Art Museum here in San Francisco is finally finding its legs after moving across town, because their members have been participating more and they’ve figured out how to persuade the tourists to pay to see their exhibits. But they had a real struggle for a long time and it’s still a challenge. I think that the larger museums think very hard about how they are going to make themselves attractive to members and tourists. I’ve been watching the development of the Lucas Museum in LA with great interest because they’re kind of doing a real elaborate version of the broccoli and cheese thing where they’re luring people in with Star Wars. They’re doing this really space-age building and, in the lobby, they’re going to have some very Instagrammable things like a giant Death Star prop that everybody’s going to line up to take their picture with. Then they hope once people are in the building they will explore the other galleries with storyboards, narrative art like Norman Rockwell, and comic art like R. Crumbs’s Genesis. For most museums that are focused on comics or narrative art, the biggest challenge is figuring out how to get people in the door. And once people start looking, then it’s like, “oh, yeah, I loved those cartoons.” A lot of the foundations that give fine art grants still have that old high and low perception too, you know, they would rather fund another Lichtenstein show than one about the artists whose work he appropriated.

NWN: Well, speaking of high and low, do you think that will ever be resolved? Or is it inherent in the nature of the medium to have that dichotomy with cartoon art as low and fine art high?

KM: At this point, there are a lot more exhibitions, especially now that graphic novels have branched out all over and there are all kinds of people doing incredible biographies and histories. People are so visually oriented now that comics are really the perfect medium for storytelling. I think that it’s really become a non-issue in a lot of places. But in museums you are depending on where the curators were educated and what kind of work they’re interested in. Someone that’s a specialist in abstract expressionist art or contemporary conceptual art is rarely going to want to invest their time and money into a show of comics. So, it depends on the goals the institution and the curators want to emphasize. I think it’s come a long way.

NWN: Yes, definitely. throughout the book, everyone, all the essayists, speak to the art of comics, and refer to the narrative, but there’s no real discussion of the collaborative nature of comics, especially if a particular artist is working from a script or with a writer. And, as you know, this is of interest to me, because of my particular area. And to me, the very nature of comics is the narrative, and the writer can be just as important to the process. And I’m really learning about the early printing process in the 30s. And how that contributed to the collaborative aspect. And why do you think that’s left out of the equation and most of the essays?

KM: Well, there are two or three things going on there. First, art exhibits are about art. Good drawing and good painting. If there’s anyone inconsistently credited in exhibits of comic book art that deserves credit, it’s probably inkers. Pencillers get the lion’s share of the credit as the art is usually their vision, but it’s often the inker that really tightened up their work, and there are colorists and letterers too. In terms of writers, most shows mention them on the wall panels and often include a reading area or something where you can see and read the final version. It’s kind of a weird conflict because writers overall still get most of the credit for almost everything involved with comics. I’ve watched my husband, an IP attorney who represents artists, negotiating these kinds of deals. Traditionally, it’s rare that artists get equal treatment with writers and actually get credit for anything. I’m glad to say that I see some improvement in that situation. In a way, representing the printing process is the same thing. Many older comics books and strips were so badly printed that seeing the actual drawings is a real revelation. For example, Jack Kirby’s collages looked kind of mushy printed on cheap paper in the comics but when you see the originals they have vibrant color and intricate detail. Curators usually try to provide some version of the finished thing, on an iPad, in a reading area, using projections, or an additional framed page.

Installation view of “Comic Book Apocalypse: The Graphic World of Jack Kirby, curated by Kirby expert Charles Hatfield at California State University Northridge. The show included pages for two entire books that were supplemented by ipads so viewers could see sketches and finished comics.

The other thing you’re dealing with is how museums understand and promote the work they are exhibiting. There’s a focus on the “lone genius,” that also undercuts this idea of collaborative work. They want to find one artist that they can point to and say “this is the guy” and not detail all the collaborators. In the book I tell the story of the Metropolitan Museum in New York buying their first Disney animation cel in 1939, a famous scene of two vultures waiting to pounce on Snow White while the Wicked Witch is showing her the poisoned apple. The curators explained to The New York Times that they credited Walt Disney for this cel, but they thought of it as the workshop of Walt Disney, the same way that you think about the workshop of Rubens or Rembrandt. You are naming the “genius,” not Stefano, the assistant who probably painted 90% of it. Lots of contemporary artists have assistants and fabricators (Jeff Koons, for example), so I think museums and curators are really used to thinking about it this way. This is a thing archives and museums that are doing historical group shows are always dealing with. Art museums are getting around this in a way because the trend is toward career retrospectives of individuals and the art of specific graphic novels, artists that often don’t have collaborators, like R. Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Dan Clowes, and Chris Ware.

NWN: I know, one of the things I noticed, because I deal with early comic book art is that there is almost disdain shown for a mainstream comics or superhero comics, as if they do not fit into an art category. But there are some really incredible artists who have worked in corporate superhero categories. Why do you think there’s that kind of disdain for that type of art?

KM: The success of the Marvel and DC movies have really helped, but most curators that accept graphic novels as a literary and artistic genre still think that superhero comics are for kids. Their mental image of superheroes is stuck in the Batman series of the 1960s where it’s total camp or they think it looks sophisticated to look down on work that is so popular with the public. Often you get around that by talking about specific artists, like Jack Kirby for instance, where you can make a case for how dynamic and influential he was. I would love to see a great Ditko show or the art of Michael Turner. I included three artists working on DC and Marvel superheroes in Women in Comics; Colleen Doran, Afua Richardson, and Alitha Martinez. But it’s still an uphill battle, even with the huge interest in Marvel right now because of the movies, not one art museum would take that big Marvel: Universe of Superheroes show that’s been touring around the country. It initially launched at the Museum of Popular Culture in Seattle, but they had a hell of a time trying to find the next couple of venues after that. Art museums weren’t interested and it’s an expensive show to present. They have had real success with science museums, who are doing that “broccoli and cheese” thing, drawing kids and their parents in with superheroes and hoping they will stay for some science. As we’re talking about this, it just opened at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. Personally, I think that there’s a lot of innovation and superhero books have really evolved with dynamic drawing, coloring, and page layouts.

NWN: In the essay that Rob Salkowitz wrote, he talks about the financial aspects of shows and how they elevate artist’s work and at the same time, many cartoonists labor under corporate control of their work or struggle to maintain independence without corporate support. Do you think there’s starting to be kind of a gatekeeper scenario within the comics world of who’s good and who’s not good and who should be elevated and who shouldn’t, maybe advanced through corporate support and so on.

KM: Well, there are two or three different issues going on here. Okay, so first of all, one of things Rob is talking about is valuation and how the cachet of a major museum show can really increase the value of an artist’s work. A lot of the time decisions about a museum’s exhibition schedule and priorities are driven by collectors that they’ve connected with, the interests of people on their board, or deals where they’ve agreed to show art for a specific time period as part of a loan or gift to the museum. It’s kind of rare for high end collectors to collect comic art. For decades, comic art drawings were considered to be an artifact of the production process and even the artists didn’t think of it as art. So, collecting comic art was kind of a fringe activity and the drawings themselves had really low valuation. Museums started to pick up on comics, because they realized that they were great reflections of the time periods they were created in and they influenced so many people. Artists that grew out of underground comix like Crumb and Spiegelman were accepted by museums and university galleries right from the start of their careers specifically because comix artists were seen as independent artists outside of corporate influence. That idea persists today. Over the years, the value of work by well-known artists has gone up. I think the current sales record was set by the sale of an R. Crumb Fritz the Cat page for $717,000 in 2018 through Heritage Auctions. So, that’s a big development. The other part of your question about corporate control I want to point out is that there are so many different ways that comics get made. I rarely see publishers getting directly involved in sponsoring exhibits other than the Marvel show or situations where a publisher owns a gallery, like Fantagraphics. If you’re talking about DC superhero comics or syndicated strips from King Features, I think it’s true that these corporate entities have a lot of control in terms of the content that is created, and sometimes you need permission to show or promote that work. Often, they will help promote an exhibit because it helps them too, for example DC spent a lot on promotion when the San Diego Comic Con Museum established a character hall of fame and did a big Batman show in 2019. Still, a lot of the artists that are getting major gallery shows are doing graphic novels as individuals, so I think the main thing is that you need to have a champion for your work that can actually explain why it should be exhibited and who the audience is because museums make a huge investment in their exhibit calendar, and that show is going to drive all of their publicity and public programming for a year. They have to be able to visualize the t-shirt in the museum store and be convinced that the art is a fit with their audience and it’s worth the financial risk to them.

NWN: I was struck by the essay by Benoit Crucifix and his discussion of Art Spiegelman’s and Dan Clowes’s work. I love Dan CIowes’s work. I’ve been a huge fan of his for a long time and of course, Art Spiegelman, but in his discussion, it was like there was almost a tendency to separate the comic art into high and low, almost a mirror of the way the art world is defined comics. I mean, that just kind of struck me a little bit.

Installation view of “Art Spiegelman’s Private Museum” at the Angouleme Festival, which included videos of him talking about the importance of the work he selected to represent his influences and heroes.

KM: Since exhibitions are temporary and location specific, everybody can’t see everything, so first let me explain a bit about those two shows. Benoit is writing specifically about shows curated by Art Spiegelman and Dan Clowes that showed work by their own comics heroes or that was influential on their own careers. So, some work is more valued than others but the point of these shows is about giving the viewer insight into the process and education of two respected artists. Spiegelman’s “private museum” was a companion show to his retrospective at the Angouleme Festival, showing things from his own collection. Eye of the Cartoonist offered Dan Clowes the opportunity to show anything he wanted from the collection of the Billy Ireland archive, which was displayed next door at the Wexner Center. If there’s a high and low here, it’s sort of the typical thing, curators have to choose what they think is important and explain why they are picking that thing and not something else.

NWN: Well, let’s move on to fans. And how do you think fans affect the trends of comic art? And also, what about cosplay? Is it art or not?

KM: First of all, the fans. There was a long thread post on The Comics Beat after Masters of American Comics that I really wish I could have included somehow, because it was a great example of how fan choices help drive these discussions. Heidi McDonald wondered how high the bar still was for women cartoonists to be included as one of the 15 geniuses in a show like Masters. The post continued with a sort of comics cage match where you could suggest someone that should be in Masters but you also had to specify which of the 15 artists you would kick out to make room. This commentary went on for about 80 posts, and it was all people talking about their favorites, and why they should have been included, and poor Lyonel Feininger just got really slammed because almost everybody thought he had an influential but very short career in comics and he could be replaced. The conversation around Masters was so influential because fans and critics were really passionate about who they thought were worthy of being in that show and why. That whole discussion launched a bunch of other shows featuring artists who were missing from that show, shows of women cartoonists, black cartoonists, artists outside of the mainstream and all of them were in some way responses to Masters. Twenty years later, people still want to argue about it. Every time I present at the Popular Culture Association’s convention and mention it, people will stand in the hallway with me for half an hour afterword still arguing about who should have been in that show. So, fans definitely have a big place in that discussion, especially now that we’re having those discussions online, and people can see them. Along with the fans, I also included critics that wrote about these shows, because the range of critical opinion is usually a pretty good barometer of where things are going.

To the second part of your question about cosplay, you and I actually saw a great cosplay exhibit at the San Diego Comic Con Museum, one of the few I thought handled it right. But I think cosplay is kind of a difficult in museums, because most of the time cosplay really needs to be seen on a person and in motion. I usually see cosplay more in the fashion show/runway format. It’s an area to explore. Fashion has become another huge draw for museums, who have had blockbuster success with designers like Dior and McQueen or themed shows like the costumes of David Bowie or of The Supremes. I especially want to point out a very important show called Superheroes: Fashion and Fantasy that was organized at the Met in 2008. Basically, the Met went to every fashion designer in New York and asked them to design their version of superhero costumes, then they did an amazing runway show of them. The catalog itself is really inspiring and it has a great essay by Michael Chabon on costume and identity. If someone is into cosplay, there are still lots of videos of that show on the Met’s site and on YouTube.

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxKlloWvppg

NWN: Yeah, that sounds really great. What are some of the exciting exhibits you have seen since the book?

KM: Well, my book came out during the Covid shut down, so really nothing. But one good trend that I’ve seen coming out of all of this is video tours of comics shows in Europe, where new shows are still opening because a lot of the European museums have been open to limited visitors. These are 3D tours you can “walk through” online and stand in front of a drawing to see the detail. You can get a pretty good feel for the exhibit. And I hope that even after museums open again, that more places will do that. Because exhibits are temporary, and most shows don’t get catalogs or any written material that really gives you an idea of what the show is like. A good exhibit is like a whole environment designed to bring out the best in the work. So, I hope these kinds of online tours are something that’s going to remain after COVID.

NWN: Yeah, it’s interesting how COVID has affected so many things. It has forced some really great innovations that hopefully will last. You had a situation with an exhibit at the beginning of this whole ordeal.

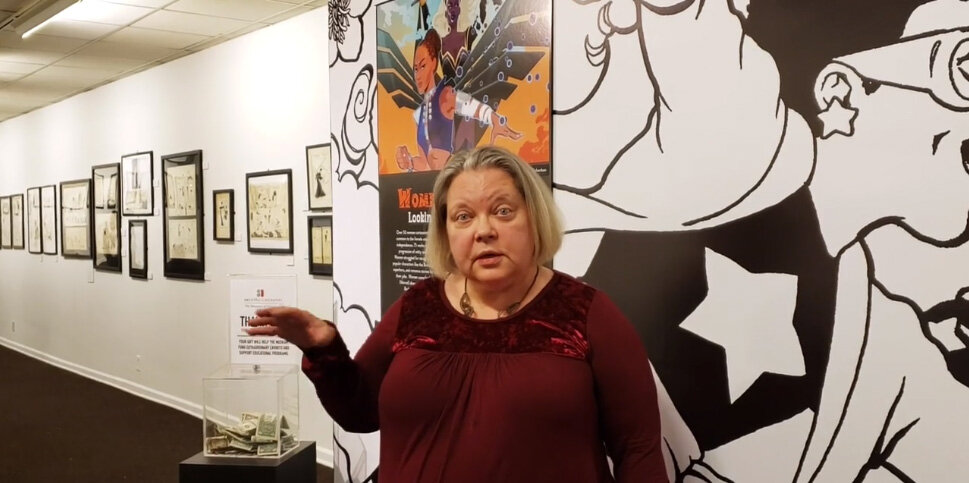

Kim A. Munson at the Society of Illustrators in New York, talking about “Women in Comics: Looking Forward and Back” right before the gallery was forced to close due to covid.

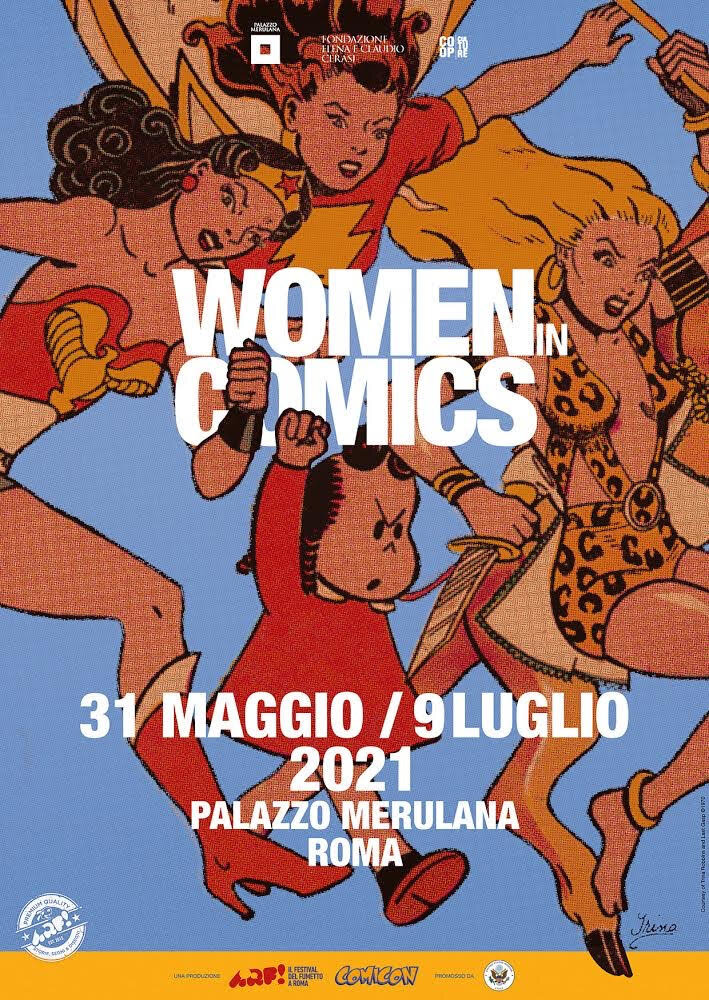

KM: I had the honor of being invited by the Society of illustrators in New York to curate an exhibit called Women in Comics: Looking Forward and Back. The Society’s main gallery is two floors. The first floor had almost 100 pieces from the fabulous historical collection of Trina Robbins starting in 1911 with a couple of beautiful Nell Brinkleys through the undergrounds in the 70s. And then the second floor had a selection of work from 21 contemporary artists that are working in all genres of comics, editorial cartoons, comic books, graphic medicine, graphic novels, web comics, a wide range of genres and voices. Anyway, what happened was the show was supposed to open last year on March 11th. I was at San Diego Comics Fest, where I was on a great panel about the fine art of comics with Rob Salkowitz, Liam Sharp, Bill Sienkiewicz, and Scott Dunbier from IDW. On Sunday, I left and flew to New York to install the show. It took us two or three days to hang everything. While I was there the whole COVID thing really came to a head and the city started to shut down around me. I hung out in the gallery on the 11th and talked to the few people that came. I got back to San Francisco on March 13. The show was forced to close the same day and stayed closed until September. They were able to keep it up through October and then they had other commitments and had to take it down. I’ve got a version of the Women in Comics show opening in Rome at the end of May as part of the big ARF! Festival there that is showing 7 pieces from 70’s work like All Girl Thrills and Girl Fight and contemporary drawings by Lynda Barry, Gabrielle Bell, Colleen Doran, Trinidad Escobar, Joyce Farmer, Margot Ferrick, Emil Ferris, Mary Fleener, Ebony Flowers, the late Noel Franklin, Lee Marrs, Alitha Martinez, Barbara Mendes, Summer Pierre, Afua Richardson, Fiona Smyth, Ann Telnaes, Carol Tyler, and Kriota Willberg. The Italians have had to really, really reassure me, you know, that yes, museums are open in Rome for limited visitors on weekdays. Now they are having a terrible surge and shutting down again. I have this terrible fear of sending all this work to Rome and nobody will see it.

NWN: Is there any information about the New York show online?

KM: I’ve collected together a lot of information on my website, neuroticraven.com. There’s a page of exhibit photos, an overview, artist bios, a zoom video of a curator talk with Trina and I moderated by Rob Salkowitz, and an artist talk moderated by me with Colleen Doran, Emil Ferris, Lee Marrs, Ebony Flowers, Trinidad Escobar, and Alitha Martinez.

NWN: Yeah, this is amazing in terms of historical moments, this whole COVID thing, what happened with you. Really incredible. So, what do you see or hope to see in the future?

In the New York “Women in Comics” Exhibit, a display of art from Women’s Comix of the 1970s from the collection of Trina Robbins, showing work by Robbins, Barbara “Willy” Mendes, and Jewelie Goodvibes from “All Girl Thrills #1.” The center mural shows Wonder Woman having a conversation with Robbins drawn by Ramona Fredon (1985).

KM: You know, I hope to see an amazing wide range of shows available about comics and different aspects of comics, the history and all of the influences and the inspirations that people have. I mean, there’s just such a wide range of stories being told now. But almost all of these people have some kind of historical influence they found in earlier comics. I’ve mentioned that I’m doing this show in Rome, one of the reasons we’re doing it was that a woman who’s in the Cultural Affairs Department at the US Embassy there saw an article about the show in The Guardian. She explained that they have great women cartoonists in Italy, but they don’t have the same historical progression from the women’s movements of the 60s and 70s through alternative comics in the 80s to today’s graphic novels. As an art historian, I really appreciate it when contemporary shows include some of the historical underpinning that inspired people. People need to understand that these things don’t just happen in a vacuum. I hope we will see more venues for historical comics shows outside of archives and libraries because people love to see these old comics and audiences would really appreciate seeing them.

NWN: I really just want to encourage anyone who’s interested in comics and comic art, that this is a wonderful book. And there’s just so much, it’s very rich. For me, it has been a wonderful way to have a better vocabulary to talk about the art. So, if you write about comics, if you’re a comics historian, this is a really wonderful introduction to the whole aspect of comic art, and comics as art. So, thank you. This is great. Really great.

KM: You’re welcome. Thanks a lot for doing this.

Check Kim’s website at Neuroticraven.com for news about artist and curator talks.